Sandra Bezic, Choreography Award

Sandra Bezic: Loving the process

by Lynn Rutherford

As Sandra Bezic tells it, her groundbreaking choreography career is largely built on one word.

“I just said ‘yes’ to everything,” she says, without a trace of regret.

“I started working just as skating was becoming so popular in North America. Living through that in the ‘80s and ‘90s, being around when the phone just never stopped ringing, I learned on the job, and one job would inform the next. I would take what I learned and apply it …. I love the process, I love to figure things out.”

For “jobs” ranging from countless programs for top skaters, to film and TV productions including Carmen on Ice and Battle of the Blades, to touring productions, Ice Theatre of New York honors Bezic with its 2024 Choreography Award.

“Sandra is one of the most intelligent, prolific and successful ice choreographers of our time,” says ITNY founder Moira North. “We are so honored to bestow this award.”

The Toronto native’s skating journey began in the 1960s, when she and older brother Val formed a pair team. The youngsters trained at the famed Cricket Club alongside the theatrical and thrilling Toller Cranston, sharing the six-time Canadian men’s champion’s coach, Ellen Burka.

Burka, a tough taskmaster who emphasized artistry and beauty along with technique, instilled the importance of selecting meaningful and personal music.

“We would go to her house and she would show us the album and tell us about the composer and what the history was,” Bezic told Canadian Press when Burka died at age 95 in 2016. “She made you understand and love the music before you started working with it, rather than just plopping it on our laps.”

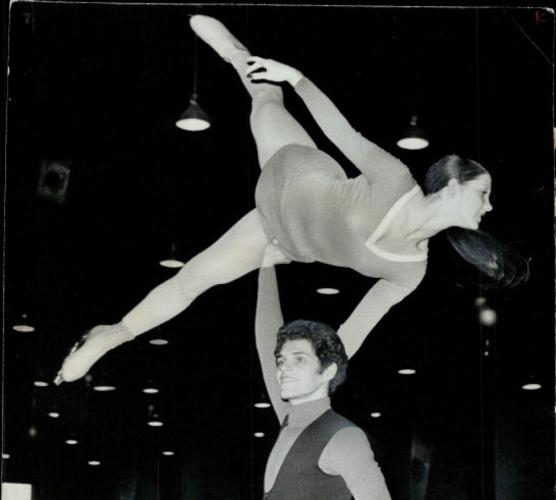

Elegant and musical, Sandra and Val won five Canadian pair titles (1970-1974) and placed in the world’s top ten four times. After they retired from amateur competition, they performed as professionals for several years.

Bezic recalls Romeo and Juliet on Ice, a 1983 TV special starring Olympic champion Dorothy Hamill, as her first big choreography gig.

“The director, Robert Iscove, was a dance director, and he asked me to ice his vision,” she says. “I was hired as an assistant, but my position grew as we worked. I learned so much from Rob, and so much about working for the camera. And that information I learned, and that perspective I learned, I then applied to my competitive programs.”

Nowadays, when skaters and their coaches await marks in the kiss-and-cry, the skaters’ choreographers are often seated alongside them. But prior to the 1980s, many skaters did not use choreographers, and if they did, they were often from the dance world. Creators of even the most memorable programs were mostly unknown to the public.

When Bezic began choreographing competitive routines, starting with four-time Canadian pair champions Barbara Underhill and Paul Martini, she was acknowledged as an essential member of the team.

“I had only just started working, and I got a call from Louis Stong, and he asked me if I would coach Barb and Paul with him,” she says. “This is before skaters had choreographers; in the competitive world, coaches did the choreography. It was perfect for me, because I was a pair skater and I was familiar with that world.”

Bezic created the programs that helped Underhill and Martini win the 1984 world pair title. She went on to create many memorable programs for them during their professional career, adhering to Stong’s directive to “go big or go home.”

“I learned my craft with them,” she says. “Barb and Paul had all the technical ability and all the tricks, but because they were so physically mismatched (due to a foot difference in height), it was a project to figure out what body lines looked good on them, and how they could relate to each other.”

The young choreographer’s phone continued to ring. In 1987, it was Linda Leaver, coach of Brian Boitano, on the line. Boitano had just been dethroned as world champion by Canadian Brian Orser, and he would be squaring off against Orser again at the 1988 Olympics in Calgary, Alberta.

That season, Boitano performed his free skate to a rather incongruous medley including “When the Saints Come Marching In,” “Summertime” and “Jailhouse Rock.” Bezic recognized his underlying majesty and breathtaking power.

“His material may have been sort of typical of what was expected – you know, when judges and officials come in to assess a skater and say, ‘Oh, you need to smile more,’” she says. “He was trying to listen to all those pieces of advice, and I felt it was making him look small. He was something different. His technique was an art form in itself.”

Bezic’s programs, including Boitano’s free skate to music from the “Napoleon and Josephine” TV miniseries, helped lead him to Olympic gold by transforming him into a compelling, larger-than-life figure on the ice, a persona he would retain for the rest of his long career.

“I was so drawn to his idealism, his single mindedness, the purity of his desire to skate the performance of his life at the moment it counted most,” Bezic says. “I wanted to give him something as grand as he seemed, to me, to be.”

The phone rang more and more. The goal, always, was to hold a mirror up to a skater and have them recognize their unique beauty and strength.

For 1992 Olympic champion Kristi Yamaguchi, Bezic’s programs emphasized “her quiet power – I wanted to uncover that.” Tara Lipinski, just 15 when she won Olympic gold in 1998, was given routines that capitalized on her youthful exuberance: “She was so young and talented. And that was all it was. (The programs) were honest.”

Four-time world champion Kurt Browning created many of his famous professional routines, including his iconic “Singin’ in the Rain,” with Bezic: “There was a real challenge in that because he can be such a chameleon …. I wanted to live up to his talent. TV specials gave us massive opportunity to play and to try different things.”

In the 2000s, as the 6.0 judging system gave way to the more regimented International Judging System (IJS), Bezic increasingly pivoted away from competitive choreography to other projects.

“My style is to peel back to find the essence of who I’m working with, instead of adding on and on,” she says. “And the rules today are sort of, the more you move around, and the more you do things, the more points you get.”

She served as a commentator for NBC for four Olympics (2002, 2006, 2010 and 2014). As choreographer, director and co-producer, she was an integral part of the “Stars on Ice” tour’s glory years, winning an Emmy for a TV production of SOI in 2003.

Battle of the Blades, a reality competition teaming figure skaters with hockey players to perform pair programs, debuted on CBC Television in 2009. It ran for four seasons and was briefly revived in 2019.

“That was an idea that was hatched in my kitchen,” Bezic says of the show. “It took us (including co-creator Kevin Albrecht) three years to get it on the air. I think all my experience in past productions was very helpful to make it happen, but of course, it’s the team, it’s never me alone.”

In 2023, she jumped headfirst into a truly quirky project, Canadian comic Carolyn Taylor’s I Have Nothing. The six-part documentary series, available on Bell Media’s streaming service Crave, follows Taylor as she interacts with figure skating champions and fulfills a childhood ambition to choreograph a pairs program to the Whitney Houston hit. Bezic acts as her mentor.

“I’m a producer, and I make TV shows and that’s the world I’ve been in far more than competitive skating and choreography,” Bezic says. “I’m far more inclined to do something like Carolyn Taylor’s show than to work with a competitor. It’s just where my brain is right now.”

But then the phone rings, and exceptions are made. Last May, Bezic traveled to Hackensack, New Jersey to create a short program for Lindsay Thorngren, an 18-year-old U.S. competitor and world junior medalist.

An introspective performer, Thorngren prefers to display emotion through subtle movements on the ice. Together, the two discussed possible music choices, much as Bezic did with her coach more than four decades ago. Bezic selected Michel Legrand’s “Windmills of Your Mind,” and Thorngren found Venus’ rendition of the classic.

“I told Lindsay, ‘There is nothing wrong with being quiet,’” Bezic says. “Quiet can run deep. I don’t believe in trying to change skaters. What I’ve always tried to do is to find a clue to the way they are most comfortable expressing themselves.”

“I feel like the music highlights my skating qualities and reflects my own thoughts,” Thorngren says. “By doing that, it helps me reach out to the audience, and helps the audience understand more about my program.”

The relationship continues. This spring, Bezic, along with David Wilson, created another program for Thorngren.

“There’s always a way to create something fresh,” Bezic says. “The unknown excites me, and I think that’s why I’ve last so long and had such a variety of experiences.”